Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS | More

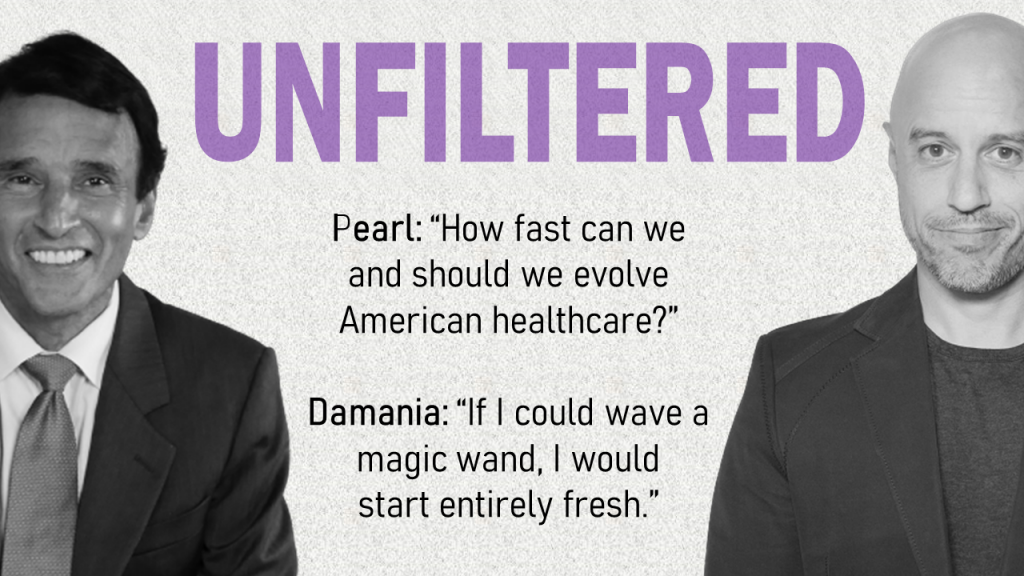

Welcome to Unfiltered, a new show that brings together two iconic voices in healthcare for an unscripted, hard-hitting half hour of talk.

Twice, Dr. Robert Pearl has appeared on The ZDoggMD Show (see: here and here) opposite Dr. Zubin Damania, who hosts of the internet’s No. 1 medical news and entertainment show. And twice before, Damania had appeared the Fixing Healthcare podcast with Pearl and his cohost Jeremy Corr (see: episode 1 and episode 26).

In the first episode of their new show Unfiltered, part of the Fixing Healthcare franchise, the duo dives into the differences—and similarities—between generations: from Boomers on up to Gen Z. Along the way, they discuss everything from techno-economic structures of healthcare to cancel culture to rap lyrics. Press play now or peruse the transcript below.

* * *

Fixing Healthcare is a co-production of Dr. Robert Pearl and Jeremy Corr. Subscribe to the show via Apple Podcasts or wherever you find podcasts. Join the conversation or suggest a guest by following the show on Twitter and LinkedIn.

UNFILTERED TRANSCRIPT

Jeremy Corr:

Welcome to Unfiltered, our newest program in our weekly Fixing Healthcare podcast series. Joining us each month will be Dr. Zubin Damania, known to many as ZDoggMD. For 25 minutes, he and Robbie will engage in unscripted and hard-hitting conversation about art, politics, entertainment and much more. As nationally recognized physicians and healthcare policy experts, they’ll apply the lessons they extract to medical practice. I’ll then pose a question for the two of them as the patient, based on what I’ve heard. Robbie, why don’t you kick it off?

Robert Pearl:

Zubin, welcome back to the Fixing Healthcare show.

Zubin Damania:

Dang, Robbie, I’m ready to get Unfiltered. I don’t know what that means, but we’re going to do it.

Robert Pearl:

Okay. Let’s begin in a place you love, Broadway. I had the chance to see a remarkable show called The Lehman Trilogy. It traced the history of the Lehman brothers from when the first generation came to the U.S., middle of the 19th century. And then it ended at the financial collapse in the first part of the 21st. What was most interesting was the continual clash of generation. Three brothers began in the South manufacturing clothes from cotton, but the next generation, it realized that it was more profitable to become transporters of cotton from the South to the industrialized North. Then the next generation recognizes it’s more profitable to be the financiers of industry and they start banking. Then the next generation says, “Why not expand to all businesses?” And they create the stock exchange, or contribute to its founding.

Robert Pearl:

And, finally, the company no longer at this point led by the family, introduces an array of financial products that ultimately proved to be Lehman’s downfall. What was so powerful to me was watching this inevitable clash. Each generation with the one that follows, one generation holding onto power, the other one coming of age, embracing change, and rejecting the values of their parents. I’d like to start by hearing your thoughts on this issue of the generations battling, whether it’s society overall, or how it plays out in medical practice. What are your thoughts, Zubin?

Zubin Damania:

Man, I love generational conflict because first of all, it’s entertaining. Second of all, it is an indicator of the natural evolutionary process of everything, like the entire universe unfolds this way. So you have generation one, let’s call them the boomers, for example, who did things a certain way. They were actually the rebels of their time. They pushed the envelope. In the ’60s the emergence of this sort of cultural revolution and the plurality and multiculturalism and postmodernism and all of that. They were the leading edge of that evolutionary chain. And then the generations that followed kind of emerged, and each of them takes a tact of first kind of learning what the previous generation kind of did. And then dis-identifying from it saying, “Oh, this has this many problems, and I don’t really like this, and this is not how I want to live.” And then trying to grab a foothold in something new and saying, “Okay, well, no, this is what we are.” And identifying with that.

Zubin Damania:

I think where that becomes healthy is where you integrate what the previous generation was able to do and actually say, “Yeah, that was necessary, but it’s partial. We need to keep striving for whatever truth is.” But if you don’t integrate it, if you just reject it and you never integrate it, then you’re in a difficult situation, then you have this kind of conflict. Now I think some of that’s inevitable, but some of it isn’t.

Zubin Damania:

As I started growing older in medicine and having house staff you could watch this play out. First, you have me, Gen X and then you start having millennials and you see a kind of a contrast in styles and expectations in sort of work ethic in a sense of it’s not that the work ethic isn’t there. It’s just it’s a different balance of what they want. They’re quite clear of saying, “I actually want to learn.” Whereas, we were like, “Well, whatever we need to do, we’ll do to kind of power through.” And so this kind of conflict to me it’s fascinating. I think it’s necessary to some degree, but understanding it allows us to actually transcend to a more integrative evolutionary approach to generational kind of thinking.

Robert Pearl:

One of the things that’s fascinating to me is how the events of the time so shape a group of individuals. As you mentioned, you have the boomers, they watched a man land on the moon, and President Kennedy talking about getting to space in less than a decade, anything’s possible. And Gen X this is the latchkey generation. They watched the breakup of the family. I’m not so sure anymore that this hard pushing is the best thing for people. Gen Y comes along and there’s 9/11, the world, it could collapse at any moment. And then Gen Z, the people who grew up during the 2008 recession. Now they’re moving back, look a lot more than the boomers.

Robert Pearl:

My sense is that the underlying motivation of people doesn’t change. It’s not that one generation is more purpose-driven or mission focused. No, it’s how it’s presented out. Is it going to be in the external world? Is it going to be in the family? Is it going to be an accomplishment? Is it going to be individual? And I fear a little bit, and this is overall, but medicine in particular that we personalize it in a negative way. My approach is better rather than understanding how as humans, we’re all shaped by what’s around us. What’s your sense?

Zubin Damania:

It’s like every disease is biopsychosocial. It has biomedical component. It has psychological component. It has social and technological components and environmental components. Everything in generational thinking is exactly that. For example, for me, Gen X we were shaped by our memories are the Challenger disaster, and the ’80s. And like you said, the sort of slow decline of family, the culture wars, these kind of things kind of shaped us and destabilized us to some degree, but I think that interaction with the system, the environment, the techno-economic structure.

Zubin Damania:

In healthcare, it becomes really fascinating because you have Gen Z now and Gen Y that have a very different upbringing than we did. They are digital natives. They started with an iPhone in their hand, the Gen Zers. And they’re entering a system where we have fax machines still. We have pagers still. We have this archaic set of payment models and CPT codes, and all this stuff. And they look at it and they cannot understand why this exists, and that pushback that they might feel, or might exhibit can be interpreted through the older generation’s lens as you’re just not paying your dues. You don’t understand, this is how we’ve done it. And we got stuck with this crap and you should too, but I don’t think that’s the right way to look at it.

Zubin Damania:

What we have to do is understand that both the techno-economic structures of healthcare and everything, and society have to adjust and vibrate along with the generation that’s coming into being, that’s going to be the predominance of the workforce, and all that, instead of us, like a lot of Gen X attendings now are just, “Oh my gosh, these millennials and these Gen Zers they’re impossible to deal with.” I don’t think that’s the right way to look at it at all nor is it for a Gen Z-er. It’s usually millennials looking at boomers going, “Yeah, okay, boomer, you guys wrecked everything. You guys don’t even know what you’re doing. Like, let us handle this.” That’s the wrong way to look at it too.

Robert Pearl:

I’m just so excited I have to tell you about Gen Z. If I were back in college, I’d study Mandarin, because I’d see that as what the future world is going to be rather than what was in the past. I’d be really interested in this narrowing of the line between humans and robots and seeing a world in which we actually will interact with these technologically created creatures that biologically don’t exist, and yet in so many psychosocial ways do. It’s interesting that I somehow have this view of the future rather than the view of the present and the past. I think it’s true for you too, Zubin. Am I right?

Zubin Damania:

Yeah, this merging of, so you cannot separate our tools and toys and technologies from us. We are intertwined with that. I recently had a guy named Daniel Schmachtenberger on my show. And we talked about this, that technology and society those structures feed back on the human mind. They feed back on us in ways that evolve us that are beyond our DNA, actually. Although, some of it is our DNA, methylation, and these sort of Lamarckian effects on our DNA, but the truth is even beyond that we are absolutely changed by these structures, so we ought to actually approach the future with kind of a mix of kind of techno optimism, like let’s design systems that actually encourage the kind of outcomes that we want as a people, which right now we haven’t done.

Zubin Damania:

With social media, we haven’t done that. We’ve encouraged fear of missing out. We’ve encouraged bad body image. We’ve encouraged division and polarity with those structures because they are purely incentivized by money. So we have to change those sort of incentives and structures to understand what you’re saying, right, Robbie? Like to actually respect that so that we can create a world that actually is what we want as opposed to what’s just going to happen to us.

Robert Pearl:

There’s no way we can stop the progress, and so I agree with you completely. We should be trying to shape it in the best way power and recognize that some of it is beyond our simple control. Zubin, you are a musical genius. At some point on this show I’d love to have you sing for people and rap for people, but let me ask you now just for your perspective on the evolution of music in a generational context. Elvis to hip hop to heavy metal to rap, where are we? What’s coming next? What is exciting to you in the musical world?

Zubin Damania:

Man, this is, and by the way, I’m a real crappy musician, but the bar in healthcare is quite low. So all I have to do is show up and I’m going to rap over a track, and I’m probably okay, but in the real world I would die instantly. So what I think about this is fascinating. It’s almost like karma, right? Cause and effect, like everything you do kind of ripples out and has effects on everything else. And it’s all a web of interdependency.

Zubin Damania:

So Elvis was basing his music on black music and blues and jazz, and that evolved into rock and roll, and that evolved into Prog rock, and that evolved into hip hop, and all these things kind of are interdependent. Everything is appropriating from everything else. When you talk to any good musician, the first thing they’ll do is tell you who their influences are. They never say, “Oh, I just made this stuff up from scratch.” No, they go, “No, no. I listen to this. I listen to that. I listen to this.” And they process it through their unconscious and out it comes. They open a hole in the universe. They take all this input and outcome something completely novel that’s actually made of these building blocks. So music is like that.

Zubin Damania:

So that’s why it’s funny as I get older, Robbie, I listen to new music and I go, “God, this sounds just like this, this sound just like this, this sounds just like this.” Because you start to pick out that karmic influence from all the generations before because you have the age and perspective to see it. Whereas, I think young people they’re just like, “This is my music. This is brand new. This has never happened.” And as they get older, they start to put it into the context of this evolutionary chain of music that’s beautiful. I mean, it goes back to the beginning of art the earliest Gregorian chanting, and before that cave singing, and all that, it all is this uninterrupted line as far as I see it.

Robert Pearl:

I read that unless you’re exposed to new music early in your life you’re never going to be able to embrace it. That there’s a cerebral neurobiological way that music gets incorporated into your brain, and yet you seem to keep evolving. I mean, I think the Super Bowl halftime show was one of your most favorite musical events. Is this your experience, or are you able to keep taking in the newest forms of music and finding value inside them?

Zubin Damania:

It’s a real challenge. I think that this window to novelty starts to close in our 30s. There’s been some data around that that if we’re not exposed to something new before we start hitting our 30s that novelty window closes and we’re more resistant. And some of it may just be biological conditioning. Some of it may be some other effects, but my experience is musicians who are the most open-minded they already emotionally personality wise they’re born with a set of tools, high openness to experience these kind of personality traits that allow them to be open to different things.

Zubin Damania:

And they’ll often say, “Oh, my parents played all kinds of music in the house, or my father was a musician,” or something like that. And that often opened their it’s like learning, like you said, you’d learn Mandarin. Like if you learn a bunch of languages before you’re 10, they’re really easy to learn. Once you get older the window of plasticity starts to close. It doesn’t close entirely. It never does, but it does make it harder. And I think the same is true with music. So some of the best musicians are the ones that had the most musical exposure when they were young.

Zubin Damania:

For me watching that Super Bowl show was like a take back to 1993. I was elated as a generational thing as Gen X going, “Oh, that was our music.” That was when I was in college. That’s when we were this was the edgiest, craziest music, and now it seems like classic rock it’s so crazy tame. And to watch them do it in the Super Bowl, and really crush it was just a lot of fun really kind of elating to see.

Robert Pearl:

I’ve heard that 50% of all music is about love either the unrequited love, the fulfilled love, the early love, the late love, the good love, the bad love. Does the music shape our view of relationships, or is that something, again, that we should be leading and directing?

Zubin Damania:

Ooh, what a lovely question. Man, I haven’t thought about this enough, but I’d say this, that it’s an epiphenomenon of our relationships and it also does shape our relationships. And in some ways it’s unhealthy because the concepts of romantic love often espoused in music are reductionist and a little cliche, and they don’t take into account the broad breadth of how humans are. So in a way romantic love is so interesting to begin with because you can contrast it in a meditative experience, or a spiritual context unconditional love, where you feel absolute acceptance unconditionally for all beings where we’re all one thing. And that kind of love feels very different than romantic love, which is in many ways kind of conditional and kind of dependent, and is dualistic in the sense that it has its highs, and then it has its very much lows, right? So music captures that because music is the emotional human state in a crystallized vibratory form. That’s why it triggers emotions, but it also is created by emotions in a way. So it’s mutually interdependent in my mind.

Robert Pearl:

I’m going to ask you a question that I would hesitate to ask to almost anyone else, but I’m very interested/really concerned about racism in medicine. I was at a karaoke club, believe it or not, about two weeks ago. And a lot of the songs were rap songs. And if they had come out of individuals who were white they would have been very offensive, I believe. Of course, the singers were black in this particular case. How do you view the language sitting in rap today that sits on this boundary around racism?

Zubin Damania:

Oh, that’s interesting because you’re talking about the N-word, which is used profusely, I think, in rap music. And it is, it’s not a word that say a Caucasian person, or me as an Indian American can use. It’s not a word that I think we can use. Now, in the music it’s interesting because it is in cadence, in incisiveness, in context of the experience of that community in the rap it is the perfect word in many ways. And so that’s the tension there and that’s art. Art is that kind of tension, the tension between society, between the social structures, between the weight of history, and between that performance in the present moment, right? So I think there’s no single answer to this. And if you asked 20 people they’ll all tell you different things depending on their background, their race, their own lived experience.

Zubin Damania:

I recently had a doc named Ian Tong on my show who is the chief medical officer of a company called Included Health. And he’s written extensively on race and medicine. He’s a black physician and he talked quite powerfully about his own experience. And I think what we have to do is listen to these perspectives and see how we can incorporate change in a systemic way, but at the same time we have to be careful about the reverse, where we’re starting to attack and marginalize say Caucasian people based on their race. Like we’re just assuming you’re a racist, we’re assuming this. And it just becomes this very self-fulfilling prophecy and a big mess. So I think just being open and authentic and honest in our conversations is 90% of the battle. And trying to really inhabit the other person’s lived experience and position as an empathic sort of exercise is crucial.

Robert Pearl:

When I was on your incredible podcast I think it’s the best one in all of healthcare. Congratulations on it.

Zubin Damania:

I’ll give you that honor, Robbie. Actually, my podcast kind of sucks for healthcare.

Robert Pearl:

You asked me a question about racism. We talked about the fact that early in the pandemic that when there was a shortage of testing kits that physicians under-tested black patients that when two patients came to the ER with the same symptoms, one a white patient, one a black patient, the likelihood was that the white patient got tested twice as often. And we talked about the nature of implicit bias that it’s biological most likely dating back 20,000 years we were cave people. Someone shows up at the door to the cave. We have a nanosecond to decide whether it’s someone we should welcome in and feed or throw a spear at because they’re coming to kill us. And that that biological piece isn’t an excuse for racism.

Robert Pearl:

And most importantly, that not recognizing it and not putting in place systems to be able to address it and prevent it that was racism. And I see that in medicine today. I see artificial intelligence as possibly being able to say, “Zubin, when you take care of this patient, usually you prescribe ex dose of medication. This patient you’re prescribing half of the pain medication, even though the pain is likely the same, do you want to reconsider?” And I don’t see medicine either acknowledging it. I mean, you can find it in the literature, but acknowledging it in how it’s changing. I don’t see residency building it into place. I don’t see technology coming in. I’m concerned and we’re seeing it in the data, women’s mortality who are black women in labor. We’re seeing this problem continue and actually become worse on what I’ve seen recently. Your thoughts on how we can best address racism in American medicine today?

Zubin Damania:

I mean, this is a massive topic. One thing you mentioned about AI is interesting because it’s a double-edged sword. AI is only as good as the information you feed it. And actually it can lead to perpetuating systemic bias if it’s fed information that is innately incomplete, or biased, and this has been something that’s been documented in AI in medicine too. And so what I think this is tricky because there are a lot of like sort of like when we point a temperature gun at someone’s head when they’re coming into a restaurant and we call that COVID screening, that’s called hygiene theater, right? It’s not really doing much of anything, but people feel better by having done it.

Zubin Damania:

I think some of the techniques and things that they’re doing in medicine are along those lines. They make people feel like, well, we’re doing something about race, but it’s really not doing anything. And what we really need to do is what you’re saying, which is look at our systemic structures and see, okay, are these contributing to this situation? And also we have to be careful about reductionist diagnoses of what’s going on because sometimes we’re missing a broader problem that is contributing to an outcome, right? Because we want equality of opportunity everywhere we can. And so any way we can knock down barriers to that equality of opportunity we need to look at systems that do that, but it’s hard, man. It’s really hard. And people don’t even want to talk about it because it makes them uncomfortable.

Zubin Damania:

Whereas, every time when I would round and we’d have a multiracial team, which was every time, right? I would talk about race all the time because I wanted to put it. And by the end, everyone was like, “This is our culture. This is what we do.” And even just having an open dialogue and people are afraid. I could get away with it because I’m off white, right? So I felt like, oh, I can say this. I don’t feel bad about it. I think a lot of Caucasian people feel bad about doing that. They’re nervous about it. And I think we have to get over that too. And that’s going to take some generations probably.

Robert Pearl:

I heard an interesting dialogue between two physicians. The first one, this is relative to the issue of change how fast we can make it. One said, “Rome, wasn’t built in a day.” And the other one said, “But it could have been.”

Zubin Damania:

I like that, could have. That sounds like Gen Y right there. Just get on Instagram and take a selfie of you with Rome, and there it is, it exists, it’s there in the picture.

Robert Pearl:

How fast can we, and should we evolve the American healthcare system?

Zubin Damania:

Man, if I could wave a magic wand, I would just start entirely fresh. And that includes medical education. And that includes our concept of what wellness and health actually mean because that’s a cultural and personal context. And, again, biopsychosocial, there’s a whole wave of that. So if I could do it, I would completely reboot it, so I’m in the camp of like, hey, it could have been built in a day, right? Because in a way, trying to undo these legacy systems at some point it just gets to be you’re banging your head against the wall, which we’ve been doing for quite some time.

Zubin Damania:

At the same time it’s very destabilizing to even talk like that. Markets would collapse if we suddenly did that, although we’d get a lot of our GDP back, probably. So I’m somewhere in the middle on that. I think we need real disruptive change, but at the same time, we’re going to have to work with structures that we have. And we’re going to have to work with a legacy population of healthcare professionals that have been conditioned and cultured in a system that is no longer going to exist if we do things right.

Robert Pearl:

So I’d like to return one last time to the generational questions. You have a massive following on your podcast. How many people follow your podcast now?

Zubin Damania:

Well, on Facebook, it’s about 2.5 million. YouTube, about half a million. Instagram, about half a million.

Robert Pearl:

I’m guessing you have a pretty broad population of generations, ages, et cetera.

Zubin Damania:

Yeah.

Robert Pearl:

Do you see, do you hear, do people respond differently based upon the generations, and if so, how is that?

Zubin Damania:

Yeah, actually they do. And each platform has a different age mix. Instagram skews younger. YouTube skews more male and younger. Facebook skews female and older. And they all respond to different, like, I can put the same piece out on different platforms and the response may be a viral million hits on one, and 5,000 meh with no comments on another. And so different generations do respond to different material quite differently whether it’s a music video from a certain era, or whether it’s just a topic that they’re interested in or not interested in and there are gender differences for sure. So it’s a real cross section of all of healthcare actually are following. Some of it depends, too, on what their profession is. Nurses respond differently than doctors respond differently than physical therapists respond differently than respiratory therapists. So there’s just so much diversity there. It’s almost impossible to know what’s going on so you just try to talk about stuff you care about authentically.

Robert Pearl:

In the end my conclusion based upon everything I’ve just heard from you is that everyone is motivated to make positive changes happen. It happens across generations. It happens across training and backgrounds. And I think that the separations that we have done personalizing it around your generation is a problem. My generation is right. I think it’s standing in the way and I would encourage you on your show and continuing in our conversation on this show to look at the similarities, to find the ways that the motivation is the same. The driver is the same because as you’ve said, I have had really wonderful experiences in my medical career in training residents and working with colleagues regardless of the particular year they were born. We should understand those influences, but we shouldn’t let them stay in the way. That’s my view of generations. Closing thoughts by you.

Zubin Damania:

I think that’s spot-on. I think we should embrace these differences as part of the normal evolutionary wave of how humans are and try to really, really put ourselves in each other’s shoes. So if we can really feel what it’s like growing up as I say a Gen Z, you can actually feel a lot of love and compassion for their struggle too, as well as the opportunities that they have. I think we’re in a spot to do that, but I do think that we get calcified as we get older and we’re more resistant to that kind of thing. Whereas, the younger generations, I mean, we ought to just make it a cultural norm that that’s how we behave.

Jeremy Corr:

ZDogg and Robbie, you guys talked about the generational differences in healthcare. One thing I hear frequently in many industries is that the younger generations are too self-obsessed, self-righteous and arguably fragile, especially on social media. Social media is obviously a blessing and a curse. It gives people the ability to share with the masses in a way they’ve never done before, but also to attack and cancel people for what they believe is wrong things like never before.

Jeremy Corr:

We see people raising awareness for humanitarian crises all over the globe, but also mobs of people canceling people for things they tweeted, or said back when they were in high school. People feel so righteous to band together with people and be part of a cause on social media. I mean, we’ve seen misinformation spread as well as way, way, way too much censorship on topics that later are proven to be true. What do you both feel is kind of that right mix of outspoken step, or being able to speak their mind versus censorship versus kind of how the different generations see and use social media as well as kind of some of the pros and cons about it?

Zubin Damania:

Well, this is like one of the fundamental things we really try to address on our show is this idea of social media as a technological tool that kind of, again, vibrates with each generation differently in that it really does hack our limbic system. It’s a race to the bottom of the brainstem. We have these hyper normal stimuli in the form of these social media things along with this weaponized tribalism in the form of likes, dislikes. We almost instantiate these collective hive minds based on individual neurons, which are like, dislike, that’s our neurotransmitter in these social networks.

Zubin Damania:

And so you have generations now that are being judged on dumb stuff they said when they were 13, who didn’t? If you could pull up everything and I’m sure there’s stuff somewhere circulating around that I’ve said when I was 14, I would be done in this climate. They would eliminate me from the face of the earth and the truth is that’s not okay because these are neuroplastic children at that age too, right? So they can’t be judged on that. We should be able to be our authentic selves, but we should also have to, again, deal with the consequences of what we say, but not in a way where the mob comes and cancels you. And, look, I’ve been the victim of cancellation. I’ve tried to cancel other people. It’s so seductive on social media, Jeremy. We need to change those social media incentives in order to make it a little better. I think we can absolutely do that. There’s much smarter technology out there that can be used to actually generate consensus and connection as opposed to polarization and cancellation.

Robert Pearl:

What I see is technology becomes ever more powerful whether you want to look at Moore’s law doubling every two years, and what you’re seeing right now is incredibly powerful technology that can be used for good or bad. Technology isn’t an intrinsic force around morality or immorality. It’s simply a tool that people apply and societies and civilizations have to figure out how to use it. You can think of it as a nuclear power that can generate electricity to light the homes without affecting climate across the globe, or you can think about it as a tool to destroy civilization. I think the time has really come for us to ask how do we want to use this powerful tool? I believe for the best in people. I think we under-utilize it in medicine. I think we probably over-utilize it as Zubin has said in people’s early lives. Finding the right balance will be difficult. Everyone wants a simple solution, a clean solution. It doesn’t exist. This force will happen. It will grow stronger. And we, as humans will have to decide whether we control it, or it controls us.

Robert Pearl:

Zubin, it’s been great. I can’t wait for next month. This has been a fascinating view to me of the millennials and the Gen Xers, and the boomers, and the future Gen Zs. And now the new Gen A that is coming along. The world will be very different in the future. Together I’m hoping we can make it better. And as I always say at the end of my shows together we can make American medicine once again the best in the world. Thank you for being our guest today.

Jeremy Corr:

We hope you enjoyed this podcast and will tell your friends and colleagues about it. Please follow Fixing Healthcare on Spotify, Apple Music or other podcast platforms. If you liked the show, please rate it five stars and leave a review. If you want more information on healthcare topics, you can go to Robbie’s website RobertPearlMD.com and visit our website at fixinghealthcarepodcast.com. Follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter @FixingHCPodcast. Thank you for listening to Fixing Healthcare’s newest series Unfiltered, with Dr. Robert Pearl, Jeremy Corr and Dr. Zubin Damania. Have a great day.